The Future of Radio Astronomy Using High Throughput Computing

Hannah Cheren July 12, 2022

Eric Wilcots, UW-Madison dean of the College of Letters & Science and the Mary C. Jacoby Professor of Astronomy, dazzles the HTCondor Week 2022 audience.

“My job here is to…inspire you all with a sense of the discoveries to come that will need to be enabled by” high throughput computing (HTC), Eric Wilcots opened his keynote for HTCondor Week 2022. Wilcots is the UW-Madison dean of the College of Letters & Science and the Mary C. Jacoby Professor of Astronomy.

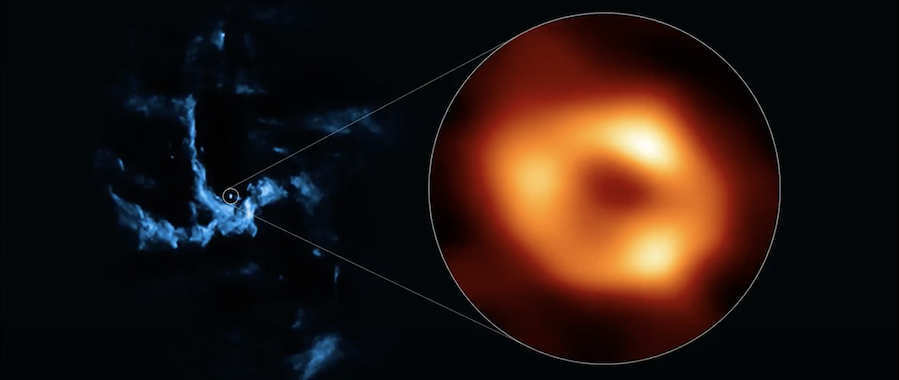

Wilcots points out that the black hole image (shown above) is a remarkable feat in the world of astronomy. “Only the third such black hole imaged in this way by the Event Horizon Telescope,” and it was made possible with the help of the HTCondor Software Suite (HTCSS).

Beginning to build the future

Wilcots described how in the 1940s, a group of universities recognized that no single university could build a radio telescope necessary to advance science. To access these kinds of telescopes, the universities would need to have the national government involved, as it was the only one with this capability at that time. In 1946, these universities created Associated Universities Incorporated (AUI), which eventually became the management agency for the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO).

Advances in radio astronomy rely on current technology available to experts in this field. Wilcots explained that “the science demands more sensitivity, more resolution, and the ability to map large chunks of the sky simultaneously.” New and emerging technologies must continue pushing forward to discover the next big thing in radio astronomy.

This next generation of science requires more sensitive technology with higher spectra resolution than the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (JVLA) can provide. It also requires sensitivity in a particular chunk of the spectrum that neither the JVLA nor Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) can achieve. Wilcots described just what piece of technology astronomers and engineers need to create to reach this level of sensitivity. “We’re looking to build the Next Generation Very Large Array (ngVLA)…an instrument that will cover a huge chunk of spectrum from 1 GHz to 116 GHz.”

The fundamentals of the ngVLA

“The unique and wonderful thing about interferometry, or the basis of radio astronomy,” Wilcots discussed, “is the ability to have many individual detectors or dishes to form a telescope.” Each dish collects signals, creating an image or spectrum of the sky when combined. Because of this capability, engineers working on these detectors can begin to collect signals right away, and as more dishes get added, the telescope grows larger and larger.

Many individual detectors also mean lots of flexibility in the telescope arrays built, Wilcots explained. Here, the idea is to do several different arrays to make up one telescope. A particular scientific case drives each of these arrays:

- Main Array: a dish that you can control and point accurately but is also robust; it’ll be the workhorse of the ngVLA, simultaneously capable of high sensitivity and high-resolution observations.

- Short Baseline Array: dishes that are very close together, which allows you to have a large field of view of the sky.

- Long Baseline Array: spread out across the continental United States. The idea here is the longer the baseline, the higher the resolution. Dishes that are well separated allow the user to get spectacular spatial resolution of the sky. For example, the Event Horizon Telescope that took the image of the black hole is a telescope that spans the globe, which is the longest baseline we can get without putting it into orbit.

A consensus study report called Pathways to Discovery in Astronomy and Astrophysics for the 2020s (Astro2020) identified the ngVLA as a high priority. The construction of this telescope should begin this decade and be completed by the middle of the 2020s.

Future of radio astronomy: planet formation

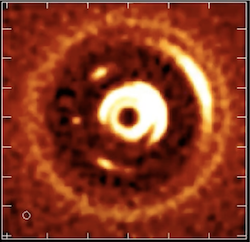

An area of research that radio astronomers are interested in examining in the future is imaging the formation of planets, Wilcot notes. Right now, astronomers can detect a planet’s presence and deduce specific characteristics, but being able to detect a planet directly is the next huge priority.

One place astronomers might be able to do this with something like the ngVLA is in the early phases of planet formation within a planetary system. The thermal emissions from this process are bright enough to be detected by a telescope like the ngVLA. So the idea is to use this telescope to map an image of nearby planetary systems and begin to image the early stages of planet formation directly. A catalog of these planets forming will allow astronomers to understand what happens when planetary systems, like our own, form.

Future of radio astronomy: molecular systems

Wilcots explains that radio astronomers have discovered the spectral signature of innumerable molecules within the past fifty years. The ngVLA is being designed to probe, detect, catalog, and understand the origin of complex molecules and what they might tell us about star and planet formation. Wilcots comments in his talk that “this type of work is spawning a new type of science…a remarkable new discipline of astrobiology is emerging from our ability to identify and trace complex organic molecules.”

Future of radio astronomy: galaxy completion

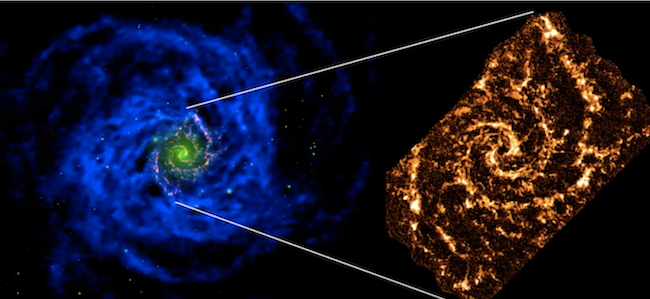

Next, Wilcots discusses that radio astronomers want to understand how stars form in the first place and the processes that drive the collapse of clouds of gas into regions of star formations.

The gas in a galaxy tends to extend well beyond the visible part of the galaxy, and this enormous gas reservoir is how the galaxy can make stars.

Astronomers like Wilcots want to know where the gas is, what drives that process of converting the gas into stars, what role the environment might play, and finally, what makes a galaxy stop creating stars.

ngVLA will be able to answer these questions as it combines the sensitivity and spatial resolution needed to take images of gas clouds in nearby galaxies while also capturing the full extent of that gas.

Future of radio astronomy: black holes

Wilcots’ look into the future of radio astronomy finishes with the idea and understanding of black holes.

Multi-messenger astrophysics helps experts recognize that information about the universe is not simply electromagnetic, as it is known best; there is more than one way astronomers can look at the universe.

More recently, astronomers have been looking at gravitational waves. In particular, they’ve been looking at how they can find a way to detect the gravitational waves produced by two black holes orbiting around one another to determine each black hole’s mass and learn something about them. As the recent EHT images show, we need radio telescopes’ high resolution and sensitivity to understand the nature of black holes fully.

A look toward the future

The next step is for the NRAO to create a prototype of the dishes they want to install for the telescope. Then, it’s just a question of whether or not they can build and install enough dishes to deliver this instrument to its full capacity. Wilcots elaborates, “we hope to transition to full scientific operations by the middle of next decade (the 2030s).”

The distinguished administrator expressed that “something that’s haunted radio astronomy for a while is that to do the imaging, you have to ‘be in the club,’ ” meaning that not just anyone can access the science coming out of these telescopes. The goal of the NRAO moving forward is to create science-ready data products so that this information can be more widely available to anyone, not just those with intimate knowledge of the subject.

This effort to make this science more accessible has been part of a budding collaboration between UW-Madison, the NRAO, and a consortium of Historically Black Colleges and Universities and other Minority Serving Institutions in what is called Project RADIAL.

“The idea behind RADIAL is to broaden the community; not just of individuals engaged in radio astronomy, but also of individuals engaged in the computing that goes into doing the great kind of science we have,” Wilcots explains.

On the UW-Madison campus in the Summer of 2022, half a dozen undergraduate students from the RADIAL consortium will be on campus doing summer research. The goal is to broaden awareness and increase the participation of communities not typically involved in these discussions in the kind of research in the radial astronomy field.

“We laid the groundwork for a partnership with a number of these institutions, and that partnership is alive and well,” Wilcots remarks, “so stay tuned for more of that, and we will be advancing that in the upcoming years.”

…

Watch a video recording of Eric Wilcots’ talk at HTCondor Week 2022.